How to Save the Lions

These Projects Protect Lions From Poachers, Traps, and Angry People

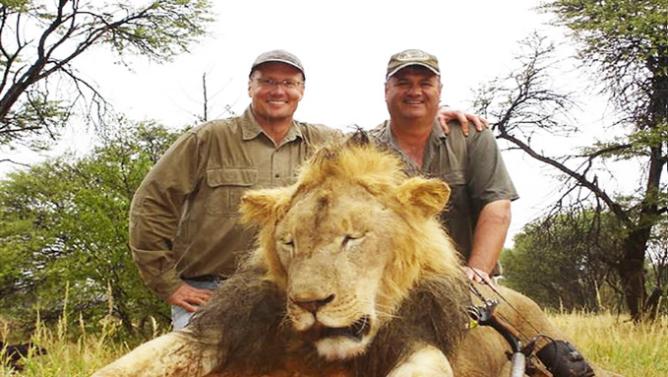

The horrific killing of the magnificent, black-maned lion Cecil by an American trophy hunter in Zimbabwe highlights the little-known plight of his species. Lion populations are in free fall, and we are losing this iconic species in most of its range. Only two centuries ago, hundreds of thousands of lions inhabited Africa. Today there are perhaps 20,000 of the big cats, living in 8 percent of their former range.

Trophy hunting is legal in Zimbabwe—although Cecil’s killing was a particularly repugnant case, in which many laws were apparently broken. Infuriating as trophy hunting may be, it is just one issue. Dozens of lions are killed each week by rural Africans in defense of their domestic cattle, goats, and camels. Many more cats die in wire snares and iron traps. Mostly laid to catch herbivores for the massive trade in wild bushmeat, illegal traps are a twofold blow for lions. Poaching devastates the wild prey that sustains lion populations. And drawn in by the distress calls of dying ungulates, lions are then captured in nearby snares themselves, where they die prolonged, ghastly deaths. As wildebeest, zebras, and antelope decline from poaching, lions resort to killing livestock, further fueling retaliatory killing by herders and ranchers.

There is a way to break this relentless cycle. We at Panthera, a big-cat conservation organization, hire locals to protect both livestock and lions. Their first job is to find lions. They do so either by the traditional method of following fresh tracks, or we train them to be para-biologists, skilled in the use of technologies like radio collars and camera traps, motion-triggered cameras that photograph lions and other wildlife as they pass by. Our lion guards keep tabs on big cats so they can chase them away from villages and communities or direct herders to graze their stock elsewhere. We also equip lion guards with training, tools, and funding to reinforce the corrals where livestock is kept overnight, when lions do most of their hunting. The lion guards provide free labor to community members, either improving traditional bomas made with local acacia thorn trees or building entirely new corrals fortified with chain-link fencing and sturdy poles. The new corrals work particularly well to protect large herds where the traditional acacia model is hard-pressed to contain 200 or 300 head of panicked cattle.

Addressing the underlying reasons that compel pastoralists to hate lions dramatically reduces their inclination to resort to bullets or poison. We went from 20 dead lions in 2013 to only one last year when we launched the program in a particularly bad conflict hot spot in northern Namibia. In communities adjacent to Zimbabwe’s magnificent Hwange National Park, where Cecil lived, only nine lion guards working with Panthera’s partners, Oxford University’s Hwange Lion Project, managed to reduce the number of killed cattle from 260 in 2010 to 73 by 2014. Living lions are the reason that we employ people—no lions, no jobs—giving people in local communities further incentive to tolerate big cats.

Tackling the issue of poaching is a more formidable challenge. Lion guards help by removing snares and discouraging people from setting them at all, but that is a stopgap. Many of Africa’s vast national parks and game reserves are desperately under-resourced—which is part of the reason their governments resort to trophy hunting to generate much-needed revenue for anti-poaching patrols. The solution is clear: more park guards, equipment, and training. Panthera and similar organizations are providing these things, but Africa’s protected areas are colossal, some the size of small countries, so protection is expensive and daunting. It will take a global response—the kind of worldwide reaction we have seen to the death of Cecil—to summon the funding and political action required to curtail poaching. If we fail, top carnivores such as the lion will be first species to vanish but not the last. Just as with overhunted tropical forests around the world, there are already large tracts of African savanna emptied of wildlife by human hunters.

Cecil would still be alive if trophy hunting had been outlawed, and perhaps this will now happen, if the global outrage over his death is any indication. However, Cecil’s species will continue to disappear unless the world supports Africa’s governments with the tremendous resources they need to secure the huge, iconic landscapes that still have lions, and the continent’s rural, livestock-owning communities in their daily efforts to live among these great cats